[NB01] Population size of selected bird species

Key message

The population trend of selected bird species is a good indicator of the long-term state of the environment. Trends in populations of selected bird species show that the state of the environment in the cultural landscape is deteriorating, while the situation in wetlands over the past few years has not changed. There is a slight decline in the populations of selected forest bird species. In recent years, populations of birds wintering along Slovenian rivers and other bodies of water are also stable. Minor fluctuations are part of natural population changes.

Definition

This indicator shows the population trend of selected bird species. In the long run, the trend is a good indicator of the state of the environment. In unfavourable conditions, populations are small, and when the conditions are good, populations are large. As birds live in various ecosystems, they allow us to determine changes in the state of the environment in the forests, cultural landscape habitats, wetland habitats, at sea, in mountainous areas and within settlements. Changes among breeding birds (spring, summer), migrating birds (spring and fall) as well as wintering birds (winter) can be observed through various bird counting methods. As birds are rather simple to identify and easy to observe, many self-taught nature lovers participate in bird counting. Thus, birds are the most commonly selected indicator worldwide for monitoring large-scale changes in the environment.

When selected species are included, the indicator shows the population of birds breeding in the cultural landscape, as well as species breeding in the forests, their trend during wintering and, especially, the trend of the common tern as an example of a colony-maintenance dependent population.

Charts

See methodology, source nr. 24,36,35,34,33,32

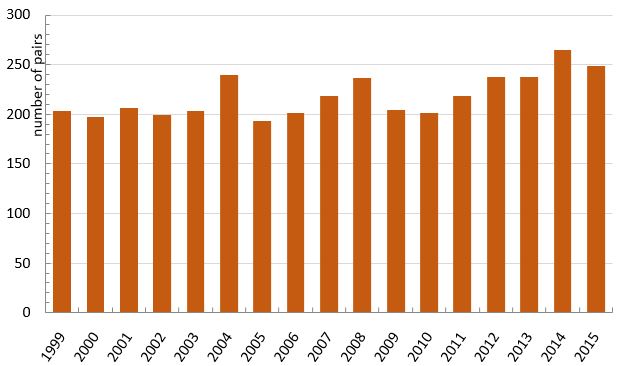

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| white stork (Ciconia ciconia | number of pairs | 203 | 191 | 201 | 194 | 199 | 238 | 187 | 192 | 218 | 237 |

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||

| white stork (Ciconia ciconia | number of pairs | 204 | 201 | 218 | 238 | 238 | 265 | 249 |

See methodology, source nr. 5, 31, 30

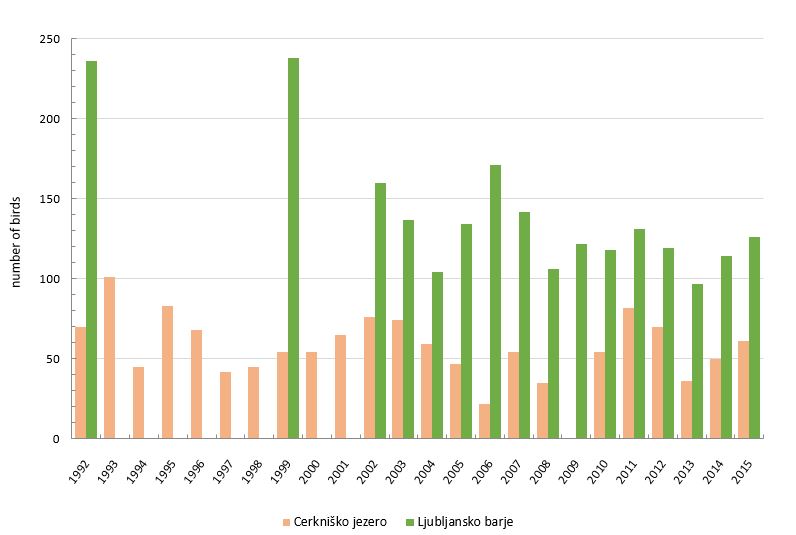

| 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerknica Lake | number | 70 | 101 | 45 | 83 | 68 | 42 | 45 | 54 | 54 | 65 |

| Ljubljana Marshes | number | 236 | 238 | ||||||||

| Slovenia | number | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||

| Cerknica Lake | number | 76 | 74 | 59 | 22 | 54 | 35 | / | 54 | 82 | |

| Ljubljana Marshes | number | 160 | 137 | 104 | 171 | 142 | 106 | 122 | 118 | 131 | |

| Slovenia | number | 0 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 277 | 0 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||||||

| Cerknica Lake | number | 70 | 36 | 50 | 61 | ||||||

| Ljubljana Marshes | number | 119 | 97 | 114 | 126 | ||||||

| Slovenia | number | 0 | 0 | 0 | 350 |

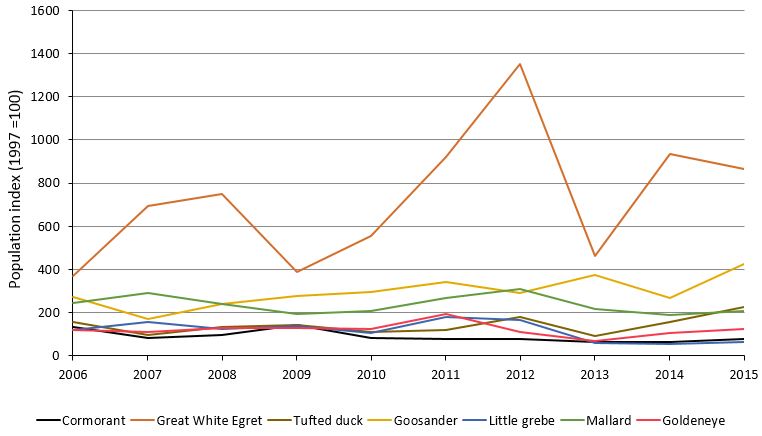

See methodology, source nr. 48, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|

See methodology, source nr. 19, 43, 44, 45, 27, 28, 29

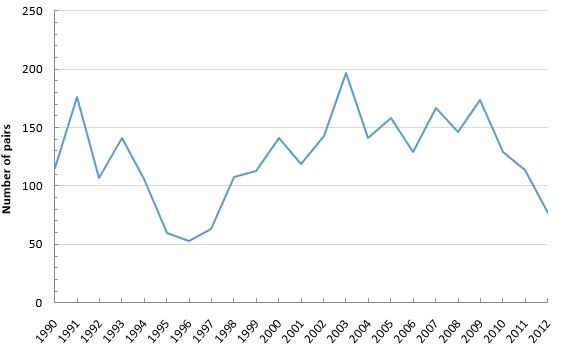

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| common tern | number of pairs | 115 | 176 | 107 | 141 | 106 | 60 | 53 | 63 | 108 | 113 |

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | ||

| common tern | number of pairs | 141 | 119 | 143 | 197 | 141 | 158 | 129 | 167 | 146 | 174 |

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |||||||||

| common tern | number of pairs | 129 | 114 | 77 |

See methodology, source nr. 31

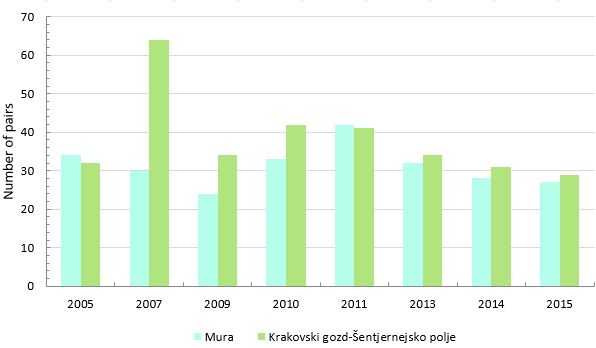

| 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mura | number | 34 | 30 | 24 | 33 | 42 | 32 | 28 | 27 |

| Krakovski gozd - Šentjernejsko polje | number | 32 | 64 | 34 | 42 | 41 | 34 | 31 | 29 |

See methodology, source nr. 31, 25, 26, 30

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2006 | 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goričko | number | 210 | 157 | 100 | |||||||

| Ljubljansko barje | number | 59 | 39 | 50 | 37 | 42 | 45 | 33 | |||

| Kras | number | 212 | |||||||||

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||

| Goričko | number | 122 | 64 | 55 | 55 | 69 | |||||

| Ljubljansko barje | number | 46 | 57 | 43 | 51 | ||||||

| Kras | number | 166 | 120 | 163 | 89 |

Goals

- To preserve a high level of biodiversity and to halt biodiversity decline by 2010.

Comment

Although Slovenia has a long-standing tradition of bird watching, the tradition of systematic data gathering is relatively new. The longest standing gathering of data has been on wintering birds on water surfaces, organised by the Slovenian Bird Watching and Research Society (DOPPS) since 1984 within the framework of the International Waterbird Census (IWC), and on autumn bird migration at the Vrhnika ornithological station near Ljubljana, carried out since 1987 by experts from the Slovenian Museum of Natural History. Most data still remain to be published. Apart from data concerning certain endangered species, the knowledge on bird migrations is unsatisfactory.

According to the existing data on bird population trends, we find that the state of the environment in the cultural landscape is deteriorating, while the conditions in wetland habitats and in forests have more or less remained unaltered. The observed fluctuations can be regarded as part of natural population changes; conversely, changes among species are more or less balanced (populations of certain species are on the increase, while populations of others are decreasing). Over the last decades, a rather significant number of bird species have disappeared from the Slovenian breeding birds list or have become virtually extinct (common snipe (Gallinago gallinago), European roller (Coracias garrulus), lesser grey shrike (Lanius minor), lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni), little owl (Athene noctua), etc.).

The population trend for bird species nesting in the cultural landscape is presented by the data gathered for three selected species: the white stork, the corncrake and the Eurasian scops owl. The white stork (Ciconia ciconia) population in Slovenia is stable. The number of breeding pairs rose in 2004 due to immigration and is not attributed to an improvement in the state of the environment. 2005 and 2006 were extremely bad years for the white stork. The number of pairs that began breeding was low and breeding success was also poor. While low reproduction in 2005 was a consequence of the very late arrival of the birds to their nesting sites (a similar phenomenon was observed in 2005 all over Europe), the poor success in 2006 cannot be ascribed to a late arrival, since the birds returned normally and in their usual numbers. The low breeding success can be attributed to highly unfavourable weather during the nesting period. It is a known fact that the breeding success of the white stork heavily depends on weather conditions. In late May of 2006, Slovenia was engulfed in heavy rains, followed by a sudden cool spell, with such weather lasting for over a week. Especially in north-eastern Slovenia, the offspring mortality rate in 2006 also incremented due to strong thunderstorms with hail physically killing off the offspring, which was recorded at various nests. In 2008, the number of nesting pairs increased again, which was followed by a decline in 2009 and 2010. In the following years, an increase in the population was recorded again, reaching its peak in 2014 (265 nesting pairs), while in 2015, the population declined slightly.

The corncrake (Crex crex) is a typical nesting bird in landscapes where extensive farming prevails. Its population has been decreasing in recent years. The corncrake population decrease in the Cerknica Lake area is small, as local farming practices have not changed considerably. The small number in 2006 is ascribed to bad weather and high water levels in the lake during the count. In the Cerknica Lake area, fluctuation in the number of corncrakes from year to year has been more or less regular. During the last national count in 2015, more singing males were counted than in 2010. In the Ljubljana Marshes, the corncrake population in 2006 fell by almost half compared to in 1992. In the period 2007–2015, the population in the Ljubljana Marshes fluctuated slightly, while generally, it continued to decline. All changes are a consequence of the transition from extensive to intensive farming, which has deteriorated the natural conditions of the environment.

The Eurasian scops owl (Otus scops) is regularly counted in the areas of Goričko, the Ljubljana Marshes and the Kras Plateau. The population in the Goričko region is declining – it has declined by 70% since 1997 and by approximately 55% since 2004. The population on the Kras Plateau also declined in the period 2004–2015. In 2014, the number of Eurasian scops owls counted on the Kras Plateau was the lowest since counting began. The population in the Ljubljana Marshes is more stable; the number in 2014 was similar to in the period 1998–2004.

The bird population trend during wintering is shown by seven selected species: the cormorant, the great white egret, the tufted duck, the goosander, the little grebe, the mallard, and the common goldeneye. The abundance of cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) has been on the rise since the species was granted protection in the previous century. It has further strengthened due to a larger amount of nutrients in organically enriched waters. The wintering population in Slovenia has remained stable over the last years. It is considered to be at the level that can be sustained by available fish. After 2009, the number of cormorants began to decline slightly. The great white egret’s (Egretta alba) population has been fluctuating considerably in recent years, but a trend of growth has been observed. The rise in abundance of the tufted duck (Aythya fuligula) may be connected to the invasion of the invasive zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) in European continental waters, which represents a rich and easily accessible nutrition source during winter. The alpine population of the goosander (Mergus merganser) has been on the rise due to a hunting prohibition, although an increased nutrition supply in organically enriched waters and installed nesting sites have probably also contributed to the greater numbers. The little grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis) population has been fluctuating or growing slightly since 1997. Since 2013, a rapid decline of the population has been observed. The populations of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) and the common goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) have been fluctuating slightly over the last decade.

As in 2005, in 2006, the common tern nested in north-eastern Slovenia at only two nesting sites: on the nesting rafts provided in the pools of the Sugar Factory near Ormož and on a newly-built 830 square metre island in Ptuj Lake. The survival of the continental population of the common tern thus entirely depends on the management of these two nesting sites. The common tern population is also decreasing due to constant competition with the black-headed gull for nesting spaces. A short-term solution to this problem is to be sought in terms of management methods, which will divert black-headed gulls from settling on the island. Since the rest of the common tern population in south-western Slovenia is also wholly dependent on artificial nesting spots, the destiny of the common tern completely depends on further management activities and available human and financial resources for this purpose. The common tern population has been in decline since 2010. In 2012, 77 nesting pairs were recorded, which was the lowest number since 2004.

The monitoring of forest birds in Slovenia is poorly developed. One exception is the hunting statistics for forest grouse species, but the field methodology for these statistics is not clearly defined. The population trend of forest-nesting birds is shown by a single selected species – the middle spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopus medius). Its numbers are systematically monitored in two IBA/SPA areas: Mura and Krakovski gozd-Šentjernejsko polje. The number of pairs in these areas has been in decline since 2011.

Methodology

The data and assessments as shown by the indicator have been derived from:

- Aleš K. (2004): Populacijski trend in izbor gnezditvenega habitata pribe Vanrellus vanellus na Ljubljanskem barju. Acrocephalus 25.

- Aleš K. (2005): Populacijska dinamika in gnezditvena biologija pribe Vanellus vanellus na Ljubljanskem Diplomsko delo.

- Božič L. (2005): Gnezditvena razširjenost in velikost populacije kosca Crex crex v Sloveniji leta 2004. Acrocephalus 127.

- Božič L. (2005): Populacija kosca Crex crex na Ljubljanskem barju upada zaradi zgodnje košnje in uničevanja ekstenzivnih travnikov. Acrocephalus 124.

- Božič L. (2006): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2004 in 2005 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 26 Božič L. (2006): Monitoring populacije kosca Crex crex v Sloveniji. Poročilo 2004 – 2006. DOPPS,

- Božič L. (2007): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2006 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus.

- Božič L. (2008a): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2009 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 29 (138/139): 169–179.

- Božič L. (2008b): Monitoring populacij izbranih ciljnih vrst ptic. Zimsko štetje vodnih ptic 2002–2008. Končno poročilo. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Božič L. (2010): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2010 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 31 (145/146): 131–141.

- Božič L. (2011): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2011 v Sloveniji.Acrocephalus 32 (148/149): 67–77.

- Božič L. (2012): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2012 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 33 (152/153): 109–119.

- Božič L. (2013): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2013 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 34 (156/157): 93–103.

- Božič L. (2014): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2014 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 35 (160/161): 73–83.

- Božič L. (2015): Rezultati januarskega štetja vodnih ptic leta 2015 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 36 (164/165): 57-67.

- (126)

- Bračko F. (1999): Navadna čigra Sterna hirundo. Acrocephalus 20 (93): 60-61.

- Čas M. (2001): Divji petelin – pokazatelj odnosa do gozda. Popis aktivnosti rastišč v Sloveniji v letih 1998-2000. Lovec 84 (6): 286-289.

- Denac D. (neobjavljeni podatki)

- Denac, D. 2001: Gnezditvena biologija, fenologija in razširjenost bele štorklje Ciconia ciconia v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 22 (106-107): 89-103.

- Denac, D. 2002: Common Tern Sterna hirundo breeding population: development and nature conservation management results at the Ormož wastewater basins between 1992 and 2002 (NE Slovenia). Acrocephalus 23 (115): 163-168.

- Denac, D. 2003a: Navadna čigra Sterna hirundo. Acrocephalus 24 (117): 76-77.

- Denac, D. 2003b: Navadna čigra Sterna hirundo. Acrocephalus 24 (119): 149.

- Denac, D. 2004: Prehranjevalna dinamika in pojav znotrajvrstnega kleptoparazitizma v koloniji navadne čigre Sterna hirundo na Ptujskem jezeru (SV Slovenija). Acrocephalus 25 (123): 201-205.

- Denac D. (2010): Population dynamics of the White stork Ciconia ciconia in Slovenia between1999 and - Acrocephalus 31 (145/146): 101-114.

- Denac K. (2000): Rezultati popisa velikega skovika Otus scops na Ljubljanskem barju v letu 1999. Acrocephalus 21 (98-99): 35-37.

- Denac K. (2003): Population dynamics of Scops Owl (Otus scops) at Ljubljansko barje (central Slovenia). Acrocephalus 24 (119): 127-133.

- Denac K., Božič L., Rubinić B., Denac D., Mihelič T., Kmecl P. & Bordjan D. (2010): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst ptic. Delno poročilo (dopolnjena verzija). Popisi gnezdilk in spremljanje preleta ujed spomladi 2010. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Denc K., Mihelič T., Denac D., Božič L., Kmecl P. & Bordjan D. (2011): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst Popisi gnezdilk spomladi 2011 in povzetek popisov v obdobju 2010–2011. Končno poročilo. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Denac K., Božič L., Mihelič T., Denac D., Kmecl P., Figelj J. & Bordjan D. (2013): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst ptic – popisi gnezdilk 2012 in 2013. Poročilo. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Denac K., Božič L., Mihelič T., Kmecl P., Denac D., Bordjan D., Jančar T.& Figelj J. (2014): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst ptic - popisi gnezdilk 2014. Poročilo. Naročnik: Ministrstvo za kmetijstvo in DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Denac K., Mihelič T., Kmecl P., Denac D., Bordjan D., Figelj J., Božič L. & Jančar T. (2015): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst ptic - popisi gnezdilk 2015. Poročilo. Naročnik: Ministrstvo za kmetijstvo, gozdarstvo in prehrano. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Kmecl P. & Figelj J. (2011): Monitoring splošno razširjenih vrst ptic za določitev slovenskega indeksa ptic kmetijske krajine – poročilo za leto 2010; poročilo za leto 2011. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Kmecl P. & Figelj J. (2012): Monitoring splošno razširjenih vrst ptic za določitev slovenskega indeksa ptic kmetijske krajine – poročilo za leto 2012. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Kmecl P. & Figelj J. (2013): Monitoring splošno razširjenih vrst ptic za določitev slovenskega indeksa ptic kmetijske krajine – poročilo za leto 2013. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Kmecl P., Figelj J. & Jancar T. (2014): Monitoring splošno razširjenih vrst ptic za določitev slovenskega indeksa ptic kmetijske krajine – poročilo za leto 2014. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Kmecl P. & Figelj J. (2015): Monitoring splošno razširjenih vrst ptic za določitev slovenskega indeksa ptic kmetijske krajine - poročilo za leto 2015. – DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Makovec T., Škornik I. & Lipej L. (1998): Ekološko ovrednotenje in varovanje pomembnih ptic Sečoveljskih solin. Falco 12 (13-14): 5-48.

- Mihelič T., Vrezec A., Perušek M., Svetličič J. (2000): Kozača Strix uralensis v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 21: 9-22.

- Mikuletič V. (1984): Gozdne kure. Lovska zveza Slovenije, Ljubljana.

- Polak S., Kebe L. & Koren B. (2005): Trinajst let popisov kosca Crex crex na Cerkniškem jezeru. Acrocephalus 121.

- Rubinič B. (2004): Raziskovalni projekti pri društvu za opazovanje in proučevanje ptic Slovenije. Svet ptic 4.

- Rubinič B. (2006): Monitoring populacij ciljnih vrst: Kako gre pticam zadnja tri leta? Svet ptic 4.

- Rubinić B., Božič L., Denac D. & Kmecl P. (2007): Poročilo monitoringa izbranih vrst ptic na posebnih območjih varstva (SPA). Rezultati popisov v gnezditveni sezoni 2007. Končno poročilo.

DOPPS, Ljubljana. - Rubinić B., Božič L., Kmecl P., Denac D. & Denac K. (2008): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst ptic. Vmesno poročilo. Rezultati popisov v spomladanski sezoni 2008. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Rubinić B., Božič L., Denac D., Mihelič M. & KKmecl P. (2009): Monitoring populacij izbranih vrst ptic. Vmesno poročilo. Rezultati popisov v spomladanski sezoni 2009. DOPPS, Ljubljana.

- Šalamun Ž. (2001): Nova gnezditvena kolonija navadne čigre Sterna hirundo v Pomurju. Acrocephalus 22 (104-105): 51-52.

- Šere D. (1989): Kratko poročilo s stalnega lovišča na Vrhniki. Acrocephalus 39-40

- Štumberger B. (1997): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 1997 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 18 (80-81): 29-39.

- Štumberger B. (1998): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 1998 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 19 (87-88): 36-48.

- Štumberger B. (1999): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 1999 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 20 (92): 6-

- Štumberger B. (2000): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 2000 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 21 (102- 103): 271-274.

- Štumberger B. (2001): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 2001 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 22 (108): 171-174.

- Štumberger B. (2002): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 2002 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 23 (110- 111): 43-47.

- Štumberger B. (2006): Rezultati štetja vodnih ptic v januarju 2003 v Sloveniji. Acrocephalus 26 (125): 99-103.

- Vogrin, M. 1991: Kolonija galebov in čiger v Hočah uničena.–Acrocephalus 12 (49): 123.

- Vogrin, M. 1991: Nova kolonija rečnega galeba Larus ridibundus in navadne čigre Sterna hirundo v Hočah pri Mariboru. Acrocephalus 12 (49): 121-122.

- Vrezec, A. 2000: Vpliv nekaterih ekoloških dejavnikov na razširjenost izbranih vrst sov (Strigidae) na Diplomsko delo, Odd. za biologijo, BF, Univerza v Ljubljani, Ljubljana.

- Vrezec, A. 2003: Breeding density and altitudinal distribution of the Ural, Tawny, and Boreal Owls in North Dinaric Alps (central Slovenia). J. Raptor. Res. 37 (1): 55-62.