[PR14] Expenditure on personal mobility

Key message

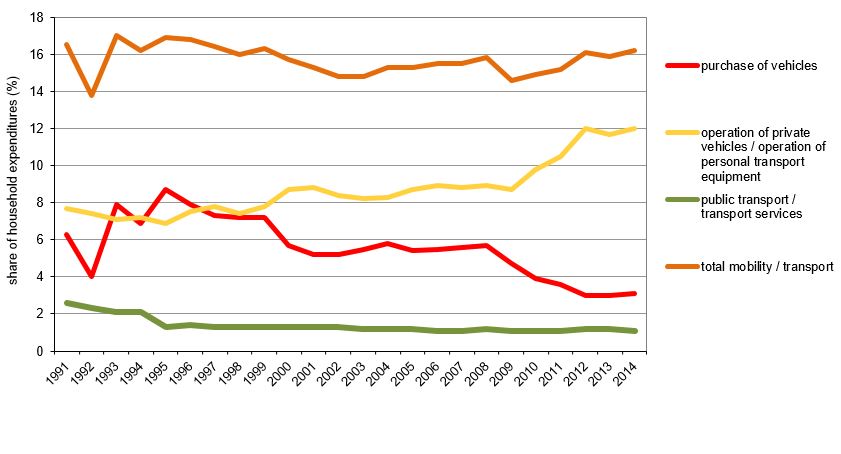

The share of household expenditure on personal mobility remains relatively stable over time. High income groups and people from economically developed countries spend more money on car purchases and personal mobility in comparison to low income groups and people from less economically developed countries. In 2014, the share of personal mobility in the expenditure of households in Slovenia was about 16%. Of this, about 12% was spent on the functioning of vehicles and about 3% on the purchase of vehicles. Only around 1% was spent on public transport.

Definition

This indicator shows household expenditure on personal mobility, which includes expenditure on purchase, operation and maintenance of private vehicles as well as expenditure on public transport. The data for Slovenia is presented for the period 1991–2014, while the data for other European countries is presented for 2012 and/or 2014.

The share of household expenditure for personal mobility is defined as the sum of household expenditure on the purchase, operation and maintenance of private vehicles and on public transport divided by total household consumption (EEA, 2015).

Household expenditure on the purchase of vehicles includes household expenditure for the purchase of new or second-hand vehicles from car dealers. Purchases of second-hand vehicles between households are not included (EEA, 2015).

Household expenditure on operation and maintenance of private vehicles includes purchase of spare parts, accessories, fuels and lubricants for maintenance or repair of private vehicles and payment of services intended for maintenance and repair of private vehicles (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2007; EEA, 2015).

Household expenditure on public transport includes the purchase of transport services relating to rail, road, air, maritime or combined transport and other transport services. Expenditures on tourist and holiday packages are excluded, while school transport services are included (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2007; EEA, 2015).

Household expenditure for personal mobility is defined in accordance with COICOP – the classification of individual consumption by purpose (Eurostat, 2000; Eurostat, 2009; EEA, 2015).

Charts

Final consumption expenditure of households by consumption purpose. Eurostat, 2015; Final consumption expenditure of households by consumption purpose - COICOP 3 digit - aggregates at current prices. Eurostat, 2016.

| 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| purchase of vehicles | % | 6.3 | 4 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 5.7 |

| operation of private vehicles / operation of personal transport equipment | % | 7.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 8.7 |

| public transport / transport services | % | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| total mobility / transport | % | 16.5 | 13.8 | 17 | 16.2 | 16.9 | 16.8 | 16.4 | 16 | 16.3 | 15.7 |

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | ||

| purchase of vehicles | % | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 3.9 |

| operation of private vehicles / operation of personal transport equipment | % | 8.8 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 9.8 |

| public transport / transport services | % | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| total mobility / transport | % | 15.3 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 14.9 |

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | ||||||||

| purchase of vehicles | % | 3.6 | 3 | 3 | 3.1 | ||||||

| operation of private vehicles / operation of personal transport equipment | % | 10.5 | 12 | 11.7 | 12 | ||||||

| public transport / transport services | % | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | ||||||

| total mobility / transport | % | 15.2 | 16.1 | 15.9 | 16.2 |

Final consumption expenditure of households by consumption purpose. Eurostat, 2015; Final consumption expenditure of households by consumption purpose - COICOP 3 digit - aggregates at current prices. Eurostat, 2016.

| Luxembourg (2012) | Slovenia (2014) | Latvia (2014) | United Kingdom (2014) | France (2012) | Germany (2014) | Austria (2014) | Estonia (2014) | EU-15 (2012) | Ireland (2014) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| purchase of vehicles | % | 5.7 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 4 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| opration of private vehicles / operation of personal transport equipment | % | 12.7 | 12 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 8.4 | 6.4 | 7 | 8 | 7.2 | 5.7 |

| public transport / transport services | % | 0.7 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| total mobility / transport | % | 19.1 | 16.2 | 11.4 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 14.2 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 12.7 |

| EU-27 (2012) | Sweden (2014) | Hungary (2012) | Italy (2014) | Denmark (2014) | Malta (2014) | Netherlands (2014) | Belgium (2014) | Portugal (2012) | Spain (2012) | ||

| purchase of vehicles | % | 3.4 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| opration of private vehicles / operation of personal transport equipment | % | 7.1 | 6.3 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 7 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.3 |

| public transport / transport services | % | 2.6 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2 |

| total mobility / transport | % | 13 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 12.6 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.4 |

| Finland (2014) | Cyprus (2014) | Poland (2012) | Czech Republic (2014) | Slovakia (2014) | Lithuania (2014) | Bulgaria | Greece | Romania | |||

| purchase of vehicles | % | 2.9 | 2 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 2.3 | x | x | x | |

| opration of private vehicles / operation of personal transport equipment | % | 6.9 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 10.6 | x | x | x | |

| public transport / transport services | % | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.1 | x | x | x | |

| total mobility / transport | % | 12 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Goals

- To introduce fair and efficient pricing in mobility and transport by internalising external costs of transport and integrating sustainable development principles that include the transition to sustainable mobility and environmentally friendly modes of transport (European Council, 2006; EEA, 2015) and

- To integrate environmental issues into transport policy (European Council, 1998; EEA, 2015).

Goals relating to personal mobility expenditure are mostly associated with pricing policies, i.e. setting fair and appropriate transport prices based on a chosen mode of transport (EEA, 205). There is a close link between income and personal mobility expenditure, which is why this needs to be taken into account in the pricing of transport used for personal mobility. Increasing transport prices is likely to lead to a decrease in transport demand and, consequently, reduced pressures on the environment. Conversely, decreases in transport prices are likely to lead to increased demand for transport and increased number of passengers. Transport pricing may thus not only be a tool to reduce the environmental pressure of transport, but also an important tool for transport demand regulation (EEA, 2015).

Goals relating to personal mobility expenditure are indirectly specified within:

- changing unsustainable and promoting sustainable production and consumption patterns (Communication, 2008a),

- reduction of consumption through the development of alternative, more energy efficient and sustainable products and resources (Sixth Environmental Action Programme, 2011),

- changing consumption patterns in personal and public expenditure in order to achieve more efficient resource management (The Road to a Resource Efficient Europe, 2016), and

- improving and providing more environmentally acceptable products and services on the European market (Environment Action Programme to 2020 - 7th Environment Action Programme, 2016).

Goals relating to personal mobility expenditure are also specified in the White Paper on Transport (White Paper, European transport policy for 2010: time to decide) from 2001, where provisions on payment of external costs of transport by users are particularly important. In 2008, the European Commission adopted the Strategy for the internalisation of external costs (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – Strategy for the internalisation of external costs) where it is stated that prices in the transport sector should reflect its actual costs paid by a society (European Commission, 2008; EEA, 2015). One of the main ideas pointed out in the strategy is that environmental damage should be paid by those causing it, which is why mobility and transport pricing should reflect the external costs of transport, which vary considerably between individual transport modes (Communication, 2008b; EEA, 2015). Internalisation of external costs should lead to inclusion of all (mostly environmental and social) costs that occur within the transport sector. As a result, mobility and transport prices should increase (EEA, 2015).

Comment

There is a close link between the income of households and individuals and their expenditure for personal mobility. In general, people spend a relatively stable share of their income on mobility. Seeing this link, higher transport prices will lead to less transport and, consequently, reduced pressures on the environment. Conversely, price decreases will lead to an increased demand for transport and environmental pressures. When household income grows faster than transport prices (which is especially characteristic in recent years), transport becomes more accessible to different groups of users, which increases the volume of transport. Personal mobility expenditure provides an insight into transport demand, which is one of the most important driving forces in transport. Therefore, prices of transport services may contribute to improvements in the state of the environment through improved management of transport demand (EEA, 2015).

Transport pricing may thus not only be a tool to reduce the environmental pressure of transport, but also an important tool for transport demand regulation. The internalisation of external costs, which is a Commission objective from the White Paper (European Commission, 2001), will make people pay for the transport costs generated. Initially, this will increase the costs for the user, as the costs of air pollution, climate change and accidents will have to be covered. In the longer term, however, the effect on transport prices will be reduced, since, due to adaptations, changed transport modes and decreased transport demand, pricing policies will reduce the magnitude of external effects (EEA, 2005).

In Slovenia, the share of household expenditure on personal mobility has been constant (16% of household budget) over the last fifteen years. Most mobility funds are used for the purchase and operation of private vehicles; a significantly smaller share is intended for public transport. In 2014, 12% of household budgets were spent on the operation of private vehicles, 3.1% on the purchase of vehicles and only 1% on public transport. The share of expenditure on personal mobility is relatively stable in other EU countries as well. Slovenia is among the countries with the highest share of funds spent for this purpose. Only Luxembourg was ranked ahead of Slovenia in 2012 according to this criterion. In 2012, Slovenian households spent 16.2% of their budgets for transport; households of the other EU-27 countries spent on average 13% of their budgets for the same purpose. In 2012, Slovenian households spent one third (30%) of their budgets on the purchase of vehicles and the operation of private vehicles (EU-27 countries 34%); at the same time, Slovenian households spent a significantly smaller share of their budgets (1.2%) on public transport in comparison with households in the EU-27 countries (2.6 %). It needs to be pointed out that, compared to expenditure for the purchase of vehicles and operation of private vehicles, the share of expenditure on public transport is minimal in the EU-27 countries as well as in Slovenia .

The share of expenditure on personal mobility appears to increase with income, which can largely be attributed to the purchase of passenger cars. Despite the fact that prices of passenger cars in European countries dropped by approximately 20% in the period 1996–2008, the share of expenditure intended for the purchase of vehicles decreased by only 15%. As wealthier people are more inclined to purchase vehicles as luxuries and status symbols, the greater share of mobility expenditures can be attributed to these factors. In expenditure intended for the operation of private vehicles and public transport, the differences between income groups are significantly smaller. Although the share of expenditure on personal mobility is roughly the same across income groups, a certain link between income and expenditure on personal mobility does exist. For example, expenditure on personal mobility is much lower for households without a car, a situation more common in the lower income groups (EEA, 2011). Differences also exist between social groups, retired and older persons spending less for personal mobility than those employed (EEA, 2015).

The share of household expenditure intended for personal mobility is also subject to other factors, such as the level of economic development of a country and settlement patterns. Households in economically more developed countries spend more on personal mobility. The size of a country as well as population density and distribution also play an important role. In the Netherlands, expenditure on personal mobility is 2% lower than in economically comparable countries (Germany, Great Britain, France). High population density and widespread use of bicycles contribute to a lower car ownership rate and lower expenditure on public passenger transport (EEA, 2015). If the share of income allocated to personal mobility is constant across different groups of society, increasing the transport prices (internalisation) becomes a useful tool for governments to influence transport volumes. It is also believed that people not only spend a roughly stable share of their budget on transport, but also a stable share of their time. As a consequence, travel speed also becomes an important determinant of transport demand, along with costs (EEA, 2015).

As the share of expenditure on operation of private vehicles has been increasing in recent years, which is largely a consequence of a higher car ownership rate, the increase of transport prices in order to reduce the volume of transport is neither sufficient nor entirely efficient. This is particularly evident in higher income groups in which growth of transport costs is not reflected in a reduced volume of transport – instead, mobility expenditure tends to increase, while the same level of personal mobility is retained. On the other hand, lower income groups react by choosing cheaper transport modes and reduced volume of transport. Thus, particular attention needs to be given to selecting appropriate pricing policies, as they can be socially exclusive when improperly planned (EEA, 2015).

Another important issue needs to be pointed out: transport policy instruments that reduce the negative environmental impact of motor vehicles (for example, the introduction of more efficient fuels), while simultaneously reducing the costs of transport users will sooner or later create a rebound effect. With reduced expenditures on personal mobility, users will still spend the same share of their income on mobility and simply drive more. This creates the possibility that the volume of transport and environmental pressures will not be reduced but may even increase (EEA, 2011).