[VD15] Groundwater recharge

Key message

Total renewable groundwater quantity in the shallow aquifers of Slovenia in the hydrological year 2018 was above the long-term average period 1981–2010.

Definition

This indicator is expressed as annual groundwater recharge of shallow aquifers in a hydrological year (1 November–31 October) in all groundwater bodies for the entire territory of the Republic of Slovenia.

Groundwater is replenished by aquifer recharge, which is a complex process of water inflow into the subterranean saturated zone. Recharge is assessed by the regional water balance model and expressed as the height of water infiltrated into aquifers (mm) or the annual variability index (the 1981–2010 average = 100).

Droughts can have severe consequences for Europe’s ecosystems and citizens, and for many economic sectors, including agriculture, energy production, industry and public water supply. It is important to distinguish between different kinds of drought. A persistent meteorological drought (i.e. a precipitation deficiency) can propagate to a soil moisture (agricultural) drought affecting plant and crop growth, which may deepen into a hydrological drought affecting water resources, water quality and freshwater ecosystems. A river flow drought is characterised by unusually low river flow, which may result from a prolonged meteorological drought, possibly in combination with socio-economic factors.

Charts

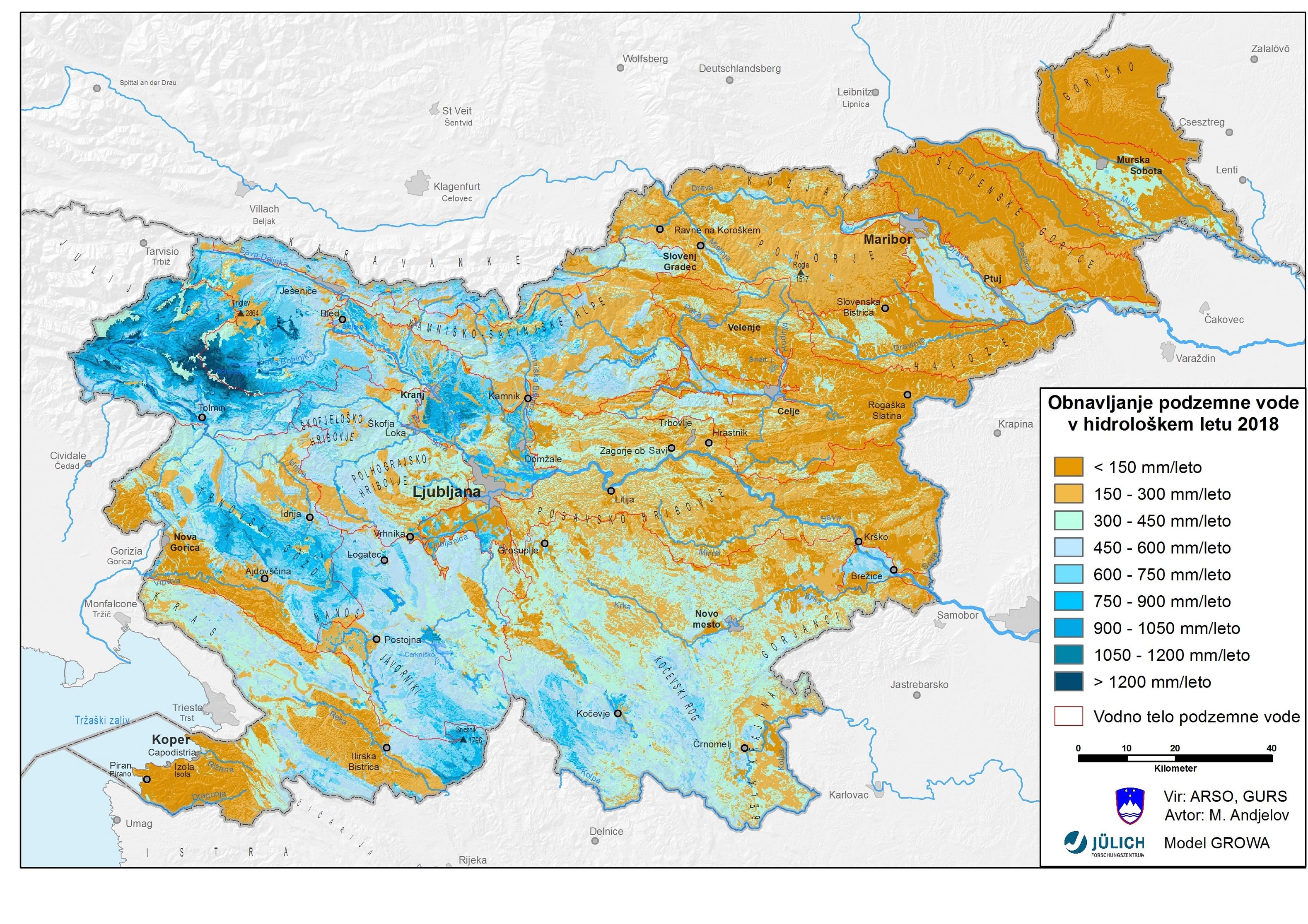

Regional water balance model GROWA-SI (Forschungszentrum JÜLICH, Slovenian Environment Agency), 2019

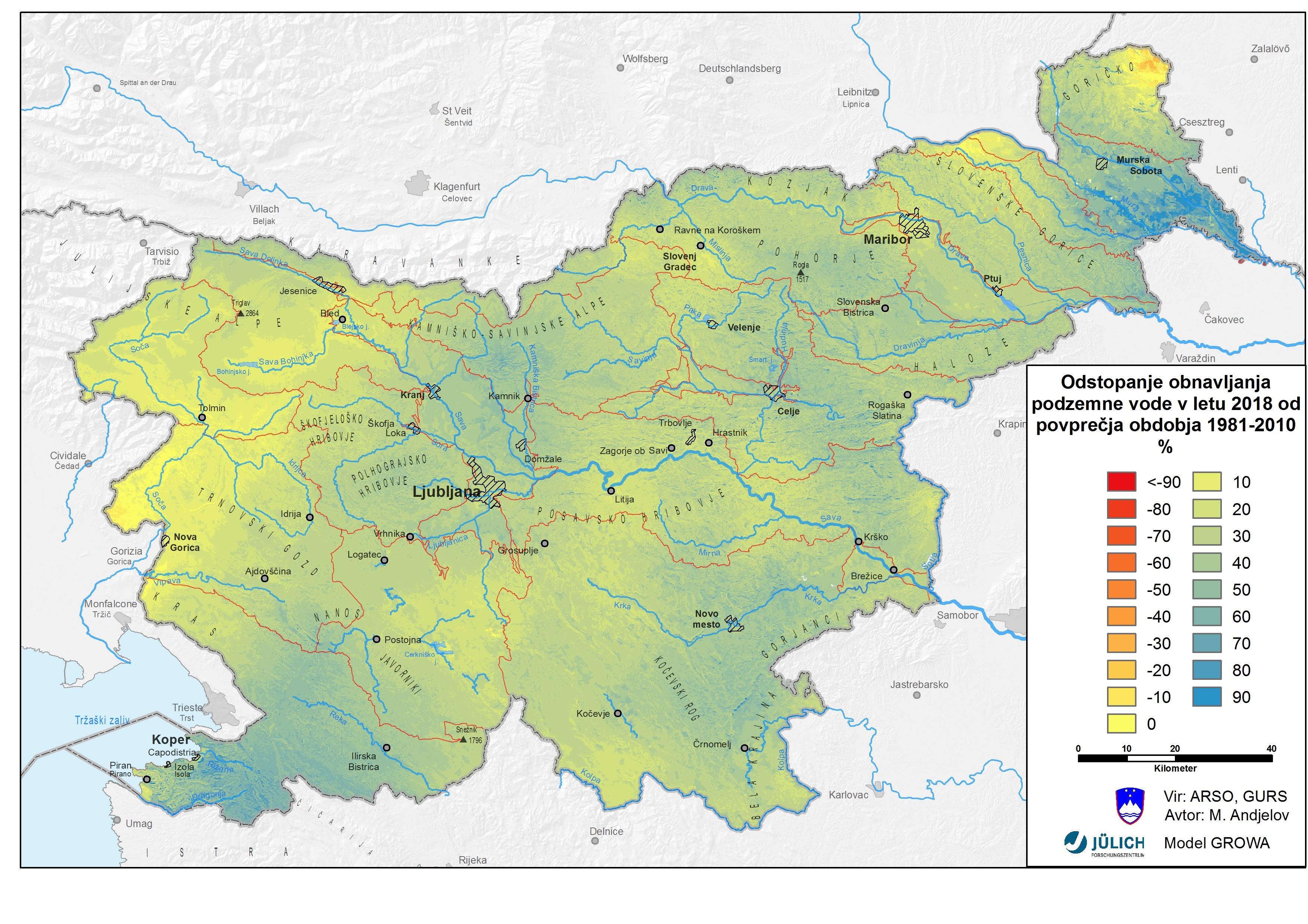

Regional water balance model GROWA-SI (FZ JÜLICH, Slovenian Environment Agency), 2019

| annual average[mm] | deviation (mm)[mm] | deviation (%)[%] | period average 1981-2010[mm] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 229.27 | -59.73 | -20.67 | 289 |

| 1972 | 384.74 | 95.74 | 33.13 | 289 |

| 1973 | 268.57 | -20.44 | -7.07 | 289 |

| 1974 | 321.26 | 32.26 | 11.16 | 289 |

| 1975 | 309.23 | 20.23 | 7 | 289 |

| 1976 | 310.48 | 21.48 | 7.43 | 289 |

| 1977 | 307.87 | 18.87 | 6.53 | 289 |

| 1978 | 311.76 | 22.76 | 7.88 | 289 |

| 1979 | 385.20 | 96.20 | 33.29 | 289 |

| 1980 | 348.45 | 59.45 | 20.57 | 289 |

| 1981 | 265.85 | -23.15 | -8.01 | 289 |

| 1982 | 326.15 | 37.15 | 12.86 | 289 |

| 1983 | 206.95 | -82.05 | -28.39 | 289 |

| 1984 | 334.56 | 45.56 | 15.76 | 289 |

| 1985 | 327.17 | 38.17 | 13.21 | 289 |

| 1986 | 276.88 | -12.12 | -4.20 | 289 |

| 1987 | 340.07 | 51.07 | 17.67 | 289 |

| 1988 | 251.75 | -37.25 | -12.89 | 289 |

| 1989 | 269.81 | -19.19 | -6.64 | 289 |

| 1990 | 311.30 | 22.30 | 7.72 | 289 |

| 1991 | 301.62 | 12.62 | 4.37 | 289 |

| 1992 | 302.55 | 13.55 | 4.69 | 289 |

| 1993 | 256.43 | -32.57 | -11.27 | 289 |

| 1994 | 275.69 | -13.31 | -4.61 | 289 |

| 1995 | 335.00 | 46.00 | 15.92 | 289 |

| 1996 | 339.20 | 50.20 | 17.37 | 289 |

| 1997 | 252.96 | -36.04 | -12.47 | 289 |

| 1998 | 299.92 | 10.92 | 3.78 | 289 |

| 1999 | 313.62 | 24.62 | 8.52 | 289 |

| 2000 | 307.66 | 18.66 | 6.46 | 289 |

| 2001 | 272.77 | -16.23 | -5.62 | 289 |

| 2002 | 276.59 | -12.41 | -4.29 | 289 |

| 2003 | 183.78 | -105.22 | -36.41 | 289 |

| 2004 | 337.16 | 48.16 | 16.66 | 289 |

| 2005 | 282.46 | -6.55 | -2.26 | 289 |

| 2006 | 222.50 | -66.50 | -23.01 | 289 |

| 2007 | 242.83 | -46.17 | -15.98 | 289 |

| 2008 | 339.92 | 50.92 | 17.62 | 289 |

| 2009 | 320.93 | 31.93 | 11.05 | 289 |

| 2010 | 399.55 | 110.55 | 38.25 | 289 |

| 2011 | 174.29 | -114.71 | -39.69 | 289 |

| 2012 | 206.80 | -82.20 | -28.44 | 289 |

| 2013 | 333.30 | 44.30 | 15.33 | 289 |

| 2014 | 461.36 | 172.36 | 59.64 | 289 |

| 2015 | 300.76 | 11.76 | 4.07 | 289 |

| 2016 | 262.70 | -26.30 | -9.10 | 289 |

| 2017 | 266.30 | -22.70 | -7.85 | 289 |

| 2018 | 358.10 | 69.10 | 23.91 | 289 |

Regionalni vodno-bilančni model GROWA-SI (FZ JÜLICH & Agencija RS za okolje), 2019

Goals

Groundwater is traditionally the major source of drinking water in Slovenia, contributing most of the required quantities in the country. Slovenian groundwater sources exhibit high regional and seasonal variability and, lately, there has been a tendency toward more frequent and more pronounced extremes. This points to the possibility of a crisis in drinking water supply in the future.

The legislative basis for the preparation of the indicator is the EU Adaptation Strategy Package, which also aims to improve the data base for better decision-making in the field of adaptation to climate change. The followint actions are required:

- improvement of groundwater quantity assessment, as well as forecasting and alarming in case of hydrological extremes, e.g. hydrological drought in aquifers;

- identification of groundwater areas prone to frequent hydrological droughts;

- improvement of groundwater management in the fields of drinking water supply and conservation of groundwater-dependent aquatic ecosystems.

Comment

The lowest recharged quantities as well as the highest variability in year-to-year groundwater recharge in shallow aquifers were recorded in groundwater bodies of northeastern Slovenia and in the Primorska region (Figure VD15-1). In the recent decade, the average recharge of aquifers in the Goričko region was 10-times lower than that of aquifers in the Julian Alps. Apart from this highly pronounced spatial variability, great variability over the course of time was recorded in the recent decade. Compared to the average for the 1981–2010 period, the index of annual groundwater recharge shows great variability, indicating high sensitivity of shallow aquifers in terms of groundwater quantity.

In the hydrological year of 2018, the total rechargeable groundwater quantity in shallow aquifers of Slovenia was markedly above the 1981–2010 average (Figure VD15-2). The average deviation for the entire territory of Slovenia is 24 %. The largest positive deviations from the average of the period 1981-2010 were in the groundwater body of the Mura Basin, where they also reach a 60% deviation. A larger positive deviation also occurs in the groundwater bodies Obala and Kras with Brkini. Elsewhere in Slovenia, the deviation ranges between 10 and 25 %. A slightly smaller negative deviation occurs in the west of Slovenia (up to -10%) and in the extreme northeast (up to -20%).